Astronomy has not been easy for me. I had an inkling of this going in. I knew that I had a hard time getting myself interested in things who's direct effect I cannot see.

Ironically, considering the subject of my speech, the one area where I seem to do fine with the invisible or ineffable is in the humanities. If it has to do with people and the way we relate to each other I have no problem getting as abstract as possible.

Astronomy seemed to me about the farthest I could go from my comfort zone and that's one of the reasons I took the class.

It turned out this was only partially the case. I eventually found my way in by conceptualizing much of astronomy through the lens of philosophy. Astronomical discoveries had such huge implications they where often paradigm shatters in regards to how we perceive reality. Learning about these different ideas and contemplating there implications was a joy for me.

Even more fascinating to me was the level of abstract thought required to grok astronomical concepts. The idea, for instance, that we can know things through mathematics that we later find provable through our senses has some mind boggling implications as far as the power of the human mind goes. It's also a total trip to think about.

As we reach the end of the semester and I begin my review for finals I'm starting to realize just how much I'm going to miss learning about astronomy (not that I'll have to stop). I feel like I'm just starting to get the hang of how to think about these things. Although, I'm still shaky on some of it, I feel like I've now got a much better grasp of the way things outside our atmosphere work. I'm hoping I'll be able to hold onto this and use it understand future developments in astronomy. I read a lot of science news. In the past I'd skip over anything having to do with astronomy of astrophysics, I'm hoping those days are done.

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Monday, May 13, 2013

I Can't Imagine How David Bowie Feels

Beyond the how awesome to hear this song actually sung by a person is space, the video it's self is pretty breath taking. The visions of earth are amazing but the part that really gave me goose bumps was all the zero gravity movements.

Everything seems so serene. Personally the idea of being up there stuck on that thing has always filled me with dread. This video made me understand a bit how someone could actually stay sane up there.

I spent a little time following different youtube links and watching this guy. He's pretty great. He's also the guy who wrung the washcloth out earlier this month.That video was even cooler than this one.

Watching all these videos I really started thinking about how gravity operates in space. In each one he lets his guitar or microphone go and it sort of floats and moves about. What makes it do that? Obviously some of it is inertia and I imagine there isn't really "zero gravity"anywhere, but still these objects seem to have a mind of their own.

Wednesday, May 8, 2013

From the Aether

Spent today's public transit time reading up on the Theory of Relativity. I was looking for lay reactions to the E=MC² equation and it's implications of the uniformity of stuff. I ended up spending way more time reading the lead up section of this wiki page:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_special_relativity

It's pretty fascinating stuff. I never realized how accepted and ingrained the concept of aether was. I guess my reference point for is has always been Victorian mysticism. Reading this article I realized that it was actually an accepted and tested scientific phenomenon. From a modern perspective it seems absurd to believe that there's something which permeates the universe against which we could measure objective speed but reading all the actual work that was done under this assumption it starts to make sense. What's even more interesting is that, from what I can gather, the current theory of relativity may not have been developed without previous work that proved, or assumed, the existence of aether. It's as if this entirely non existent thing was needed as training wheels to get us to the a place where Einstein could develop his theory.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_special_relativity

It's pretty fascinating stuff. I never realized how accepted and ingrained the concept of aether was. I guess my reference point for is has always been Victorian mysticism. Reading this article I realized that it was actually an accepted and tested scientific phenomenon. From a modern perspective it seems absurd to believe that there's something which permeates the universe against which we could measure objective speed but reading all the actual work that was done under this assumption it starts to make sense. What's even more interesting is that, from what I can gather, the current theory of relativity may not have been developed without previous work that proved, or assumed, the existence of aether. It's as if this entirely non existent thing was needed as training wheels to get us to the a place where Einstein could develop his theory.

Thursday, May 2, 2013

Pillars of Creation

Just looked up what exactly the Pillars of Creation are. I guess the term refers specifally to this photo taken by the Hubble Telescope in 1995:

This is a picture of giant gas clouds in the Eagle nebula. They are in the process of creating stars which is why they where called the "Pillars of Creation". They are also apparently being eroded by the light of nearby stars in a process called photoevaportation, which I had to look up.

Interestingly, the Pillars of Creation are actually neither creating new stars nor being eroded because, most likely, they no longer exist. They where destroyed by a shock wave from a super nova. In fact they where destroyed 6000 years ago but since they are 7000 light years away from us we see them in their still extant state.

This is a picture of giant gas clouds in the Eagle nebula. They are in the process of creating stars which is why they where called the "Pillars of Creation". They are also apparently being eroded by the light of nearby stars in a process called photoevaportation, which I had to look up.

Interestingly, the Pillars of Creation are actually neither creating new stars nor being eroded because, most likely, they no longer exist. They where destroyed by a shock wave from a super nova. In fact they where destroyed 6000 years ago but since they are 7000 light years away from us we see them in their still extant state.

Wednesday, May 1, 2013

Animals and Phones in Space

There where two interesting little blurbs in the Science Tuesday section of the Times yesterday. The first was about sending animals into space, the other was about sending smart phones into space.

The smart phone one was pretty cool. They sent up standard Google Nexus One phones ups and had them send images back to determine whether this technology can be used in satellites. The phones are named Alexander, Graham and Bell. Which is a nice coincidence considering they just released recording of Alexander Graham Bell's voice that had been lost for over a century.

The animals flight was much more interesting. They sent up gerbils, mice, geckos and snails to test the effects of prolonged space flight on living creatures. The best part is that they will be studying the sperm of the mice to try and determine how possible it would be for people to re-produce in space. This means we're one step closer to the a "space arc".

The Times makes a point of noting that the animals are expected to survive re-entry, the phones will not.

The smart phone one was pretty cool. They sent up standard Google Nexus One phones ups and had them send images back to determine whether this technology can be used in satellites. The phones are named Alexander, Graham and Bell. Which is a nice coincidence considering they just released recording of Alexander Graham Bell's voice that had been lost for over a century.

The animals flight was much more interesting. They sent up gerbils, mice, geckos and snails to test the effects of prolonged space flight on living creatures. The best part is that they will be studying the sperm of the mice to try and determine how possible it would be for people to re-produce in space. This means we're one step closer to the a "space arc".

The Times makes a point of noting that the animals are expected to survive re-entry, the phones will not.

Monday, April 29, 2013

Stars on Film

I've been having a little bit of a hard time getting my head around some of the concepts in the life of a star so I figured I'd watch a few videos about it.

The first one to come up was this: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PM9CQDlQI0A&feature=player_embedded

It was actually pretty helpful. I think the only part I was really having trouble with was understanding the shift from hydrogen to helium fusion. I get it better now that I've seen some visual models of it. It was aslo cool to see some images of planetary nebulae which are pretty bad ass.

I think this one was my favorite

The second video I watched (http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=mzE7VZMT1z8) was pretty ridiculous. It covered pretty much the same exact material but in twice the time because it needed to do things like show an image of someone skiing or climbing a rock every time it mentioned gravity. For some reason it's creators also felt that in order to understand a galaxy filled with stars it needed to show us Las Vegas. I'm still unclear on the connection here.

The one cool thing it did talk about was the "Pillars of Creation" I'm going to look into those thing some more.

The first one to come up was this: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PM9CQDlQI0A&feature=player_embedded

It was actually pretty helpful. I think the only part I was really having trouble with was understanding the shift from hydrogen to helium fusion. I get it better now that I've seen some visual models of it. It was aslo cool to see some images of planetary nebulae which are pretty bad ass.

I think this one was my favorite

The second video I watched (http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=mzE7VZMT1z8) was pretty ridiculous. It covered pretty much the same exact material but in twice the time because it needed to do things like show an image of someone skiing or climbing a rock every time it mentioned gravity. For some reason it's creators also felt that in order to understand a galaxy filled with stars it needed to show us Las Vegas. I'm still unclear on the connection here.

The one cool thing it did talk about was the "Pillars of Creation" I'm going to look into those thing some more.

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

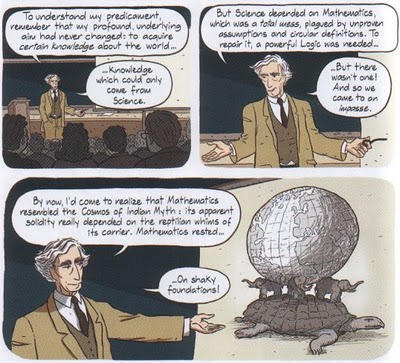

Logicomix

Just finished reading the graphic novel Logicomix about Bertrand Russel and the search for truth in logic. It was a decent comic. In truth they made a bit too much of an effort to make it accessible. They left out most of the math and technical jargon and tried to make it a story about people. By doing this I didn't feel like I could make a connection to any of their breakthroughs.

It didn't have anything specifically to do with Astronomy but it did help me come to terms with the idea mathematics as a tool for modeling the universe. I've always bristled a little bit at the idea that something we can't observe is true because the math works. Now that we've seen so many cosmic things that where described first by mathematics I'm a little more comfortable with it but I can't say I understand it. I could never accept the idea of axioms. If these are the foundation of math and logic and we are expected to believe them a priori, doesn't this require a sort of faith that logic would naturally find repellant.

This book didn't really clear up all that but it did make me feel happy that other very smart people are worried about the same thing. The book has Russel say that he's "written a 365 page book that proved that 1 + 1 = 2". I'll never read this book, apparently very few have, but I feel a little better knowing someone wrote it.

It didn't have anything specifically to do with Astronomy but it did help me come to terms with the idea mathematics as a tool for modeling the universe. I've always bristled a little bit at the idea that something we can't observe is true because the math works. Now that we've seen so many cosmic things that where described first by mathematics I'm a little more comfortable with it but I can't say I understand it. I could never accept the idea of axioms. If these are the foundation of math and logic and we are expected to believe them a priori, doesn't this require a sort of faith that logic would naturally find repellant.

This book didn't really clear up all that but it did make me feel happy that other very smart people are worried about the same thing. The book has Russel say that he's "written a 365 page book that proved that 1 + 1 = 2". I'll never read this book, apparently very few have, but I feel a little better knowing someone wrote it.

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

Galaxies

Checked out Astronomy Picture of the Day today. They had this cool picture of a galaxy up.

This galaxy is called M81 and it's one of the brightest galaxies in our sky.

The accompanying information was mostly about the little section up top that doesn't appear to be behaving the same way as the rest of the galaxy. It's called "Arp's Loop".

What was most interesting to me looking at this image was my reaction to it. I've seen images of galaxies millions of times throughout my life and never once thought about why they look the way they do. Looking at it now I know why the core is bright and why it's shaped the way it is. I know what's happening in the arms and in the core. These are thing I never thought of before. It's odd to me the things we take for granted.

This galaxy is called M81 and it's one of the brightest galaxies in our sky.

The accompanying information was mostly about the little section up top that doesn't appear to be behaving the same way as the rest of the galaxy. It's called "Arp's Loop".

What was most interesting to me looking at this image was my reaction to it. I've seen images of galaxies millions of times throughout my life and never once thought about why they look the way they do. Looking at it now I know why the core is bright and why it's shaped the way it is. I know what's happening in the arms and in the core. These are thing I never thought of before. It's odd to me the things we take for granted.

Thursday, April 11, 2013

Meteorite from Mercury

This just landed in my inbox from NPR:

http://www.npr.org/2013/04/11/176714430/origin-of-meteorite-is-a-puzzle-to-scientists?ft=3&f=122101520&sc=nl&cc=sh-20130413

It's about a meteorite that could have possibly come from mercury... although it turns out it probably didn't.

I guess it has a similar chemical makeup as Mercury. It's very low in iron which was one of the things that ruled out it coming from Mars or simply being an Earth rock.

Furthermore, it turns out that this rock has the same magnetic field as Mercury. I'm not exactly what that means but it seems pretty far out. I should do some reading on magnetic fields.

The one chink in this theory is that the meteorite is extremely old. So old that it predates Mercury being solid enough to create such rocks. The current theory is that it actually comes from the asteroid belt.

Either way this is apparently a very fascinating meteorite. There's a great slide show of a bunch of other meteorites on the page linked above. It includes a one from Mars, one from the moon, and one that's actually the oldest rock ever found. It was formed in the gas cloud that used to surround the sun!

It never occurred to me that meteorites could be from other planets. I always assumed they where just free floating rocks in space. Now that we're learning about how all this works it makes much more sense that more relatively large rocks would be formed on other planets than that they would form on their own in space.

http://www.npr.org/2013/04/11/176714430/origin-of-meteorite-is-a-puzzle-to-scientists?ft=3&f=122101520&sc=nl&cc=sh-20130413

It's about a meteorite that could have possibly come from mercury... although it turns out it probably didn't.

I guess it has a similar chemical makeup as Mercury. It's very low in iron which was one of the things that ruled out it coming from Mars or simply being an Earth rock.

Furthermore, it turns out that this rock has the same magnetic field as Mercury. I'm not exactly what that means but it seems pretty far out. I should do some reading on magnetic fields.

The one chink in this theory is that the meteorite is extremely old. So old that it predates Mercury being solid enough to create such rocks. The current theory is that it actually comes from the asteroid belt.

Either way this is apparently a very fascinating meteorite. There's a great slide show of a bunch of other meteorites on the page linked above. It includes a one from Mars, one from the moon, and one that's actually the oldest rock ever found. It was formed in the gas cloud that used to surround the sun!

It never occurred to me that meteorites could be from other planets. I always assumed they where just free floating rocks in space. Now that we're learning about how all this works it makes much more sense that more relatively large rocks would be formed on other planets than that they would form on their own in space.

Monday, April 8, 2013

Bad Astronomer

Just checked out the Bad Astronomer blog that was suggested as an option for the website review. Having taken a closer look at it now I kinda wish I'd chosen to do a review of it. This guy's writing is so much more accessible to me than the websites I did review.

I read three of his entries. One was on the above video of silly putty, which had been mixed with iron oxide, "eating" a magnet. It's a pretty cool video and the blog's author Phil Plait explains some of it's scientific implications well. Really though I just kept thinking it would be a cool thing to do with the high school kids I tutor.

The second article was about the difference in the nights sky in the southern hemisphere. Not doing much star gazing myself I didn't find this one all that interesting.

The third one though was pretty intersting. This was about a NASA mission to bring an asteroid close enough to the earth that we can study it. Plait spent quite a bit of time talking about this one. He discussed how it could be done, why it should be done, and what the obstacles are. He included the far out drawing below of one of the capture options. If I understand it correctly this will match the movements of the asteroid pull it into it's large bag thing, close the bag then make constant adjustments until the asteroid settles down.

Plait's primary conclusion was that, although this was an incredibly cool idea, it might not really be feasible.

His skepticism was based on a few factors but primarily it came down to him not believing NASA had much of a plan or the money to do it. They'd recently announced that the white house will give $100 million dollars to this project. Not much considering how much it will cost.

A couple things that caught my eye while reading this this where

1) It's really hard to see small things in space like astroids.

2) Plait seems to think that the best option to get people up to actually look at this astroid if we get it near us is SpaceX, the privately owned space program. That's pretty amazing.

3)All this stuff is so incredibly expensive. It must be surreal to be an astronaut and know that a country is spending millions of dollars on your existence every day your up there.

The second article was about the difference in the nights sky in the southern hemisphere. Not doing much star gazing myself I didn't find this one all that interesting.

The third one though was pretty intersting. This was about a NASA mission to bring an asteroid close enough to the earth that we can study it. Plait spent quite a bit of time talking about this one. He discussed how it could be done, why it should be done, and what the obstacles are. He included the far out drawing below of one of the capture options. If I understand it correctly this will match the movements of the asteroid pull it into it's large bag thing, close the bag then make constant adjustments until the asteroid settles down.

Plait's primary conclusion was that, although this was an incredibly cool idea, it might not really be feasible.

His skepticism was based on a few factors but primarily it came down to him not believing NASA had much of a plan or the money to do it. They'd recently announced that the white house will give $100 million dollars to this project. Not much considering how much it will cost.

A couple things that caught my eye while reading this this where

1) It's really hard to see small things in space like astroids.

2) Plait seems to think that the best option to get people up to actually look at this astroid if we get it near us is SpaceX, the privately owned space program. That's pretty amazing.

3)All this stuff is so incredibly expensive. It must be surreal to be an astronaut and know that a country is spending millions of dollars on your existence every day your up there.

Thursday, April 4, 2013

Dark Stuff Over Dinner

Last night I had some friends over for dinner. One of them was telling me that he'd recently become curious about Astronomy and had ordered a book online that he was very disappointed in. I told him I was taking this class and we spent a good while trying to talk about concepts that where still pretty fuzzy to both of us. Of coarse the the concepts that really caught everyone's imagination where Dark Matter and Dark Energy.

To tell the truth I did a pretty bad job explaining them and my friends seemed pretty skeptical. It was very hard for them to buy into the idea of these things as both real things and sort of place holder terms for phenomenon we're pretty sure exists but don't know anything about. The more they drank the more they liked to say "The dark matter is all around us" in an ominous voice.

I woke up this morning still thinking about it and saw this in the Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/04/science/space/new-clues-to-the-mystery-of-dark-matter.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

I kinda wish I'd had that article the night before.

To tell the truth I did a pretty bad job explaining them and my friends seemed pretty skeptical. It was very hard for them to buy into the idea of these things as both real things and sort of place holder terms for phenomenon we're pretty sure exists but don't know anything about. The more they drank the more they liked to say "The dark matter is all around us" in an ominous voice.

I woke up this morning still thinking about it and saw this in the Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/04/science/space/new-clues-to-the-mystery-of-dark-matter.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

I kinda wish I'd had that article the night before.

Tuesday, April 2, 2013

Space Collisions

Just finished listening to this little thing on the NPR website.

http://www.npr.org/2013/03/29/175741693/segment-2

This one was from last week's "Science Fridays". It was a segment about collisions and their effects on our solar system.

The most interesting part was about the creation of the moon. I'd heard before that the moon might have been formed from part of the earth but I never really understood what that meant. In particular I always imagined that some solid object, like a comet or astroid, had hit the already solid earth and sent off a chunk which became the moon.

It turns out that this was a total misunderstanding. For one thing, if the collision took place, it happened while the earth was still somewhat molten. And it wasn't a collision with a small thing, it was a collision with another planet sized thing, which was also not solid.

Even more interesting it turns out that this model isn't really supported by some current evidence. Most of what the moon is made up of is the same stuff the earth is made up of. If it was formed by a collision of the earth and another planet then the moon should be made up of some of that other planet's material.

Despite this evidence, the scientists being interviewed said he'd "bet his career that some kind of a giant impact that formed the moon". He's just not sure what kind.

http://www.npr.org/2013/03/29/175741693/segment-2

This one was from last week's "Science Fridays". It was a segment about collisions and their effects on our solar system.

The most interesting part was about the creation of the moon. I'd heard before that the moon might have been formed from part of the earth but I never really understood what that meant. In particular I always imagined that some solid object, like a comet or astroid, had hit the already solid earth and sent off a chunk which became the moon.

It turns out that this was a total misunderstanding. For one thing, if the collision took place, it happened while the earth was still somewhat molten. And it wasn't a collision with a small thing, it was a collision with another planet sized thing, which was also not solid.

Even more interesting it turns out that this model isn't really supported by some current evidence. Most of what the moon is made up of is the same stuff the earth is made up of. If it was formed by a collision of the earth and another planet then the moon should be made up of some of that other planet's material.

Despite this evidence, the scientists being interviewed said he'd "bet his career that some kind of a giant impact that formed the moon". He's just not sure what kind.

Monday, April 1, 2013

New Type of Super Nova

Just read this article about a "New Type of Super Nova"

http://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2013/03/27/175497906/astronomers-say-theyve-discovered-new-type-of-supernova

This appears to be a much smaller type than the type they use as standard candles. They do however come from binary stars just like the other ones (these ones come from binary stars with white dwarfs). Astronomers also think these ones come from much younger stars since none are found in elliptical galaxies which have less young stars.

It's interesting for me reading these articles since I now know what terms like "elliptical galaxies" and "standard candle" mean. I feel like I've always read scientific articles in mainstream press but I must of just unconsciously skipped over these words. I wonder how many words I skip over without even knowing it.

http://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2013/03/27/175497906/astronomers-say-theyve-discovered-new-type-of-supernova

This appears to be a much smaller type than the type they use as standard candles. They do however come from binary stars just like the other ones (these ones come from binary stars with white dwarfs). Astronomers also think these ones come from much younger stars since none are found in elliptical galaxies which have less young stars.

It's interesting for me reading these articles since I now know what terms like "elliptical galaxies" and "standard candle" mean. I feel like I've always read scientific articles in mainstream press but I must of just unconsciously skipped over these words. I wonder how many words I skip over without even knowing it.

Monday, March 25, 2013

The Onion's new response to the new CMB images:

http://www.theonion.com/articles/universe-older-wider-than-previously-thought,31776/

Pretty funny. My favorite response it the first one.

While studying for the midterm I realizes that the information about the universe not being uniform in all directions is not really new, it was just confirmed by the new study.

http://www.theonion.com/articles/universe-older-wider-than-previously-thought,31776/

Pretty funny. My favorite response it the first one.

While studying for the midterm I realizes that the information about the universe not being uniform in all directions is not really new, it was just confirmed by the new study.

Thursday, March 21, 2013

New Map of the CMB

Just read this article from The Guardian (the British one not the Bay Area one):

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2013/mar/21/planck-telescope-light-big-bang-universe

Pretty interesting stuff. They made some new discoveries. There's more dark matter in the universe than they thought and less dark energy. The most interesting stuff, however, is that the universe does not appear to be uniform in every direction. The article points out that this "rules out some versions of the expansion model but not all" but doesn't explain this further.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2013/mar/21/planck-telescope-light-big-bang-universe

Pretty interesting stuff. They made some new discoveries. There's more dark matter in the universe than they thought and less dark energy. The most interesting stuff, however, is that the universe does not appear to be uniform in every direction. The article points out that this "rules out some versions of the expansion model but not all" but doesn't explain this further.

Wednesday, March 6, 2013

The Love of Paradigms

The lesson today got me thinking about paradigm shifts. I've always been interested in the way scientific discoveries effect the way we think but recently I've come to realize that it's more important to look at how the way we think effects the discoveries we make.

As a religious studies major and someone very interested in biological evolution I've given a lot of thought to how the difficulty in accepting a non-human centric world has effected our sciences. It seems that no matter how much evidence we receive we still see ourselves as somehow different and above other species. We are constantly learning that other species have attributes we once thought where exclusive to humans which just seems to make us hold on tighter to few attributes that remain. This line of thought is present in most of the language used by environmentalists; we cannot "save the earth" because we're really not on the path to destroying it, we are simply on the path to making it uninhabitable for us.

This concept can be seen on a larger scale with the so called "anthropic principle" which as I understand it, states that the universe must work in such a way that life can exist since life does exist. This seems to me flawed thinking since life is really no more special than stars, space dust or radio waves. We simply believe it's special because we are it.

This has very little to do specifically with astronomy I suppose but it got me thinking about how much time and energy we lose by holding onto ideas we are comfortable with. In fact it seems that humankind is so unwilling to let go of previously held ideas "comfortable" isn't even the right word. These are ideas we are in love with.

As a religious studies major and someone very interested in biological evolution I've given a lot of thought to how the difficulty in accepting a non-human centric world has effected our sciences. It seems that no matter how much evidence we receive we still see ourselves as somehow different and above other species. We are constantly learning that other species have attributes we once thought where exclusive to humans which just seems to make us hold on tighter to few attributes that remain. This line of thought is present in most of the language used by environmentalists; we cannot "save the earth" because we're really not on the path to destroying it, we are simply on the path to making it uninhabitable for us.

This concept can be seen on a larger scale with the so called "anthropic principle" which as I understand it, states that the universe must work in such a way that life can exist since life does exist. This seems to me flawed thinking since life is really no more special than stars, space dust or radio waves. We simply believe it's special because we are it.

This has very little to do specifically with astronomy I suppose but it got me thinking about how much time and energy we lose by holding onto ideas we are comfortable with. In fact it seems that humankind is so unwilling to let go of previously held ideas "comfortable" isn't even the right word. These are ideas we are in love with.

Monday, March 4, 2013

Looking into Luminosity

From what I can tell from wikipedia, in astronomy luminosity is

"the amount of electromagnetic energy a body radiates per unit of time."

From this I gather that that during the dark age the matter in the universe was not emitting an electromagnetic energy. Since the energy must have already existed then it must not have been radiating. I'm still a little unsure exactly what that means.

Looking further into it I cam across this answer:

"most of the photons in the universe are interacting with electrons and protons in the photon–baryon fluid. The universe is opaque or "foggy" as a result. There is light but not light we could observe through telescopes."

Which I instantly recognized as something we where taught in class the day this question came up. Having now spent a little extra time with it I feel like I'm beginning to actually understand what went on.

"the amount of electromagnetic energy a body radiates per unit of time."

From this I gather that that during the dark age the matter in the universe was not emitting an electromagnetic energy. Since the energy must have already existed then it must not have been radiating. I'm still a little unsure exactly what that means.

Looking further into it I cam across this answer:

"most of the photons in the universe are interacting with electrons and protons in the photon–baryon fluid. The universe is opaque or "foggy" as a result. There is light but not light we could observe through telescopes."

Which I instantly recognized as something we where taught in class the day this question came up. Having now spent a little extra time with it I feel like I'm beginning to actually understand what went on.

Friday, March 1, 2013

What The Hell is a Magnet and What Makes Things Bright?

These two questions stuck in my mind after I left class the other day.

The first question occurred to me while I was thinking about electromagnetism. We'd just learned that most things aren't really effected by the electromagnetic force because the positive and negative forces inside them balance each other out and leave them electrically neutral. If this is so then how are magnets made? Obviously something is done to them to upset the balance but what? Do magnets occur naturally? If so where and how? Finally how do magnets work on metal that is still electrically neutral? Do they change the charge of the metal?

The second question came to me when I was thinking about the "Dark Age". If there was light in the universe by this point (assumably the same light that's in the universe now) then how come things where not visible. What is it beyond just light that make something illuminated? I've always assumed it was reflecting off things, if this is so then how solid does something have to to reflect light? What other qualities does it need?

The first question occurred to me while I was thinking about electromagnetism. We'd just learned that most things aren't really effected by the electromagnetic force because the positive and negative forces inside them balance each other out and leave them electrically neutral. If this is so then how are magnets made? Obviously something is done to them to upset the balance but what? Do magnets occur naturally? If so where and how? Finally how do magnets work on metal that is still electrically neutral? Do they change the charge of the metal?

The second question came to me when I was thinking about the "Dark Age". If there was light in the universe by this point (assumably the same light that's in the universe now) then how come things where not visible. What is it beyond just light that make something illuminated? I've always assumed it was reflecting off things, if this is so then how solid does something have to to reflect light? What other qualities does it need?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)